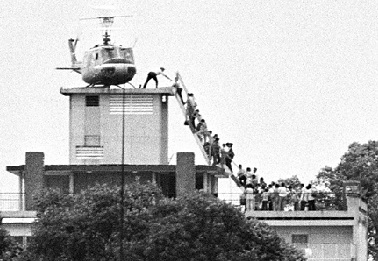

Saigon exit, courtesy of wikipedia.org.

“We make lists because we don’t want to die.” So says, Umberto Eco, medievalist, philosopher, and author of Foucault’s Pendulum. With lists, we attempt to manage time, knowing time is a nonrenewable resource. A list fixes a task to memory and gives us the psychological satisfaction of thinking the job is underway, even though, making the list sometimes is as far as a project goes. (“Undone,” by Clive Thompson, Wired, Sept. 2021, pg. 75.)

Having a goal begins our footrace against the future. Unfortunately, it is a double-edged sword. We gain the momentary satisfaction of expressing our intent but if we don’t follow through, we can be riddled with anxiety. Like Scarlet O’Hara, we tell ourselves, “I’ll worry about that tomorrow.,” But if tomorrow is slow to arrive, we feel guilty, and sometimes scarp the project. Even so, the erosion of our intentions can haunt us longer than the memory of tasks we’ve accomplished. This condition has a name: the Zeigarnik effect.

Most of us know that list-making is no guarantee we will accomplish a task. We need more than intent. We need a plan of execution and a fair assessment of the time the job will take. If the task turns out to be too great for the time allowed, we may put it off for another day. In effect, we sacrifice our future selves to appease the present one, says writer Clive Thompson. Most college freshmen know this principle. Choosing to play frisbee in the sun, they condemn their future selves to an all-nighter to meet the deadline for a class paper.

America’s foreign policy is often hampered by the same principle. We know how to get into a war but we put off planning for a graceful exit. We do it because predicting the future is difficult. We can make a list of possible outcomes for the endgame, but that’s different from having an executable plan for each.

The current chaos in Afghanistan is an example. Donald Trump’s rushed agreement with the Taliban left insufficient time to execute a successful evacuation. Equally eager to withdraw, President Biden failed to see the error until his intent met with reality. That meant the timeline had to be extended and he has hinted he may extend it again.

So far, he’s stuck with the August 31 deadline, which is a good sign. It means he’s satisfied with our progress. Let’s hope he stays that way because each deferral to the future looks like a stumble.

The media could do more to help. Its mantra, “if it bleeds it leads,” focuses them on the chaos of our withdrawal without providing much insight into the reasons. Worse, the men and women of our military receive little praise for how well they are meeting the difficulties they face and for some spectacular rescues.

Bad beginnings are no predictor of outcome, happily. Most adults remember the initial chaos of the Affordable Health Care rollout. Who’s a critic now? During the Afghan evacuation, it might be best if reporters stopped sticking microphones into the faces of terrified people to ask how they think things are going.

Biden has promised to evacuate Americans and people in Afghanistan who have a right to leave. If he keeps his word, he will also keep the word of the American people. That’s what matters.