A TALE HALF TOLD

I’ve just finished reading one of my book finds from the Dollar Store, Don DeLillo’s “Point Omega.” Normally, I wouldn’t identify the author of a work I didn’t like but DeLillo is a National Book Award winner so I’m certain my pale criticism will do him no harm.

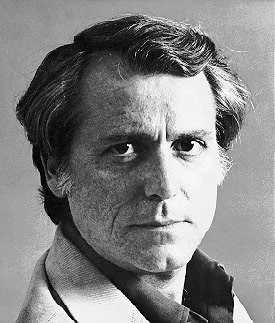

(Don DeLillo)

I’d not read any of his work before, though I knew the name and was eager to become acquainted. Unfortunately, by the time I closed the book, I could only wonder at what passes for great writing today. Here’s the plot:

A filmmaker, Jim Finley, approaches a man, Richard Elster, about a film he wants to make. The latter invites the former to his house in the desert — which desert is not identified except to say it is somewhere in the Sonoran or Mojave Desert “or another desert altogether.” (“Point Omega” DeLillo, pg. 20) The characters meet and spend the bulk of their time sitting, staring into open space. Occasionally, Elster makes a comment about the Omega point: that point where the mind and space dissolve into one another. Soon, Elster’s daughter arrives. The young woman has been shipped off by the man’s ex-wife to keep the girl out of the clutches of an unacceptable suitor. The three manage to accommodate one another, largely by ignoring each other’s presence. Then, one day, the two men drive off to replenish supplies and when they return, the daughter is missing. A search begins and lasts for several days but the girl is not found and her father’s mind begins to disintegrate. Eventually, the filmmaker decides Elster cannot stay on his own, and so he packs him off to the ex-wife, hoping she’ll care for him. End of story.

This plot, spare and unemotional as it is, is sandwiched between what I’ll call a prologue and epilogue. In both, a man – neither Elster nor Finley — spends hours at a museum where the featured exhibit is a replay of Alfred Hitchcock’s film, “Psycho,” but presented in slow motion so that it lasts 24 hours. Mostly the unidentified man stands around watching other people watching the movie, though in the epilogue he manages to obtain the phone number of a female but never discovers her name.

I admit DeLillo knows how to put a noun and a verb together. There’s no problem with his style but I couldn’t help feeling that most of the book, which is mercifully short, (117 pages) remains in his head. I can make a few stabs at what he means by Point Omega. Like “Waiting for Godot” he examines what it is to wait. But unlike Beckett’s play, nothing in the novel surprises us or threatens us at a pace that leaves us at the edge of our seats. DeLillo gives us the kind of waiting akin to that of standing in line at the unemployment office. It doesn’t puzzle us. It bores.

Perhaps a story about endless, meaningless waiting, where life is seen is slow motion, needed to be written. But in choosing “Psycho” as a starting point, I’m lead astray. DeLillo’s story is not about the fear or dread or the tension of waiting, so I see no connection between the man in the prologue and the protagonists of the main story — except that they are all waiting and staring. For me, the link isn’t good enough… isn’t strong enough.

DeLillo might say I’ve missed the point entirely and he may be right. But I say half of the novel never made it to print.