Though averse to ageism, I was moved when I read that longtime Congresswoman Anne Kuste was retiring to allow someone younger to take her place. As a tribute to her decision, I have recorded below my relevant brunch conversation with a Millennial.

***

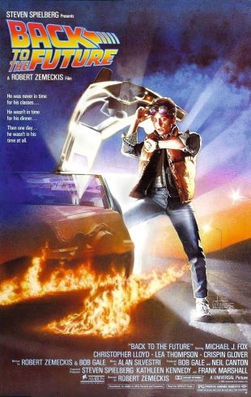

Courtesy of wikipedia.org

Sitting down at a restaurant with a young man in his early thirties, I was amused when he opened the conversation with news about a high-speed train to be built between Portland and Seattle. “Think of it,” he marveled, throwing his shoulders back against his chair. “That would make an hour commute. I could work in one city and be home in time for supper in another.”

“Life lived as a blur,” I muttered and reached for my napkin. Why were the young so enamored with speed, I wondered. My reply was that when technology propelled us forward at a supersonic rate, we risked unanticipated consequences. As evidence, I quoted Timothy Snyder. He thought that in times of change, people were seduced by the notion of hidden realities and dark conspiracies. (On Tyranny, by Timothy Snyder, Random House, 2017, pg. 89.)

My companion peered over his menu with arched eyebrows. “Are you sure you’re quoting Snyder correctly?”

“No, I’m not,” I shrugged. “But at least I live at a pace where I have time to find out if I’m wrong.”

As our waiter stood at my elbow, I interrupted my thoughts long enough to order French toast before returning to my point. “I do know Eric Hoffer said people were too willing to tear up the past so they could liberate the future. (The True Believer, by Eric Hoeffer, Harper&Row, 1959, pg. 67.) That’s the same idea, isn’t it?”

“I haven’t read much Hoeffer,” my friend, Michael,* admitted after the waiter walked away with his order for a Denver omelet. “Nonetheless, I don’t understand the connection.”

“With Snyder? Isn’t it obvious?” I shot him a look of mock surprise. “The past informs the future. Otherwise, we’d have to reinvent the world every day?”

“Yes. But what’s speed got to do with it?”

“Speed is everything,” I insisted ignoring his frown which refused to fade. “When life moves too quickly, our little brain cells can’t cope.”

“You think high-speed trains will derail us?”

Noting the frown had become a smirk, my voice notched higher. “Believe me when I say I’ve lived through many changes in my life. I can remember when there was no television, and kids played tag in the streets instead of staring at cell phones. I can even remember when we stored butter in an ice box.”

“Ah. The good old days. Is that what you mean?”

“Some of those days were good and others weren’t. But I do think children were better off running around outside than sitting indoors, twiddling their thumbs and playing video games.”

“I played video games as a kid and I don’t think it did me any harm. Probably improved my coordination”

“So could dribbling a basketball. “

“I did some of that too.”

“Okay, how youngsters waste their time isn’t the issue. I’d be the first to concede that our brains are wonderful machines capable of adaptation. The wonder is they can change yet somehow remain stable.”(“‘Our Plastic-Stable Brains,” by Cara Nixon, Reed Magazine, Winter 2024, pg. 42) But when change is too rapid, things fall apart.”

“You think fast trains will cause our brains to explode?”

“If you’d stop sneering for a minute, I could explain. I’m talking about scale. Neanderthals were lucky. They dealt with one saber-tooth tiger at a time. In the past, even wars were fought one at a time. What’s changed is technology. Now we can supersize and fight several enemies at the same time. Millions could die but are we as moved by that as the one who collapses in our arms? I’m suggesting we could lose our humanity.”

Michael paused to take a sip of his coffee, perhaps vying for time. “What about the good changes” he said at last. “No one dying of cancer would complain if a cure came sooner rather than later.”

I leaned forward, certain I had him in my sites. “Yes, but what’s one good consequence compared to many poor ones? Take Elon Musk, for example.”

I’d rather not,” Michael snorted.

“Exactly! The world’s richest man uses technology to spoil our elections and fan the flames of Nazi sentiment in Germany. And what do we do? We sit here buttering our toast.”

“Actually, the toast hasn’t arrived.”

“Be serious.”

“Okay, I grant your point about Musk,” Michael relented. “ But other billionaires are working against him. That should be a comfort.”

“Explain what you see as ‘comfort.’ A war between the oligarchs? What about the rest of us? We’ve seen Jeff Bezos’ priorities. He’d rather sell us toothpaste than tell us the truth. Look how he silenced the Washington Post’s editorial board.

“Did you ever watch The X-Files? Everyone knows ‘the truth is out there.’”

“No. You can’t get away with laughing this off. What about climate change? Is that truth out there?”

Chastened by my question, Michael sat for a moment. “That may be a problem…”

“It’s more than a problem,” I interrupted. “Fossil fuels are killing our planet. Yet, what does our incoming President say? ‘Drill, Baby, Drill.”

“Yes, but everyone knows Trump’s crazy.”

“The oil executives don’t. Nor do a majority of voters,” I parried.

“So what what do we do? Become Amish? Attempt to go back to the future?”

“A fair tax code would help.”

As we broke into laughter, the waiter appeared with our orders. Unfazed by whatever had passed between us, he set our plates down and with a warning that they were hot, left us. When my gaze fell upon my French toast, glistening with powdered sugar, I realized I was hungry. Michael must have felt the same because each of us picked up our fork without another word.

Several moments passed before our conversation resumed. When it did, we seemed more eager to catch up on one another’s news than to spar about climate change. Michael told me he was eyeing a job with someone in politics. I revealed I was working on a new book, my last.

Both of us knew we couldn’t anticipate what 2025 would bring. If the truth was “out there,” we’d have to discover it together. I needed my friend’s exuberance. And though he may not know it, he would benefit from my caution. Nature schools us in the value of symbiosis, doesn’t it? Each autumn, when the oak leaves fall, I’m sure they are meant to protect the acorns below.

When we parted at last, it occurred to me that anyone who’d overheard our earlier conversation about speed and trains would have smiled to see that Micheal had paid for his brunch with a credit card while I had laid down cash.

*The name is false

Boycott Tesla!