Courtesy of GoGraph.com

Dr. Anthony Fauci admitted he was stunned to see people of the Conservative Political Action Committee (CPAC) applaud when they learned Tennessee had halted all vaccinations for minors, including those for Covid-19. The state said it wanted to protect parents’ rights to make medical choices for their children. Critics accused Tennessee of playing politics with public health.

Many people believed Donald Trump when he compared the pandemic to seasonal coughs and sniffles. Today, those coughs and sniffles have cost 607,000 Americans their lives. Even so, Trump supporters are loyal and continue to resist taking a vaccine that will prevent the spread of the disease. Perhaps they fear if he was wrong about the illness, he might be wrong about his claim that he won the 2020 presidential election– known to others as the Big Lie.

In his book, Mein Kompf, Adolf Hitler wrote that if a lie is audacious and repeated, many will come to believe it. This is particularly true in a time of crisis. Fear drives people toward confident voices despite a senseless message. As I wrote earlier, fear encourages unity, but it also stupefies the mind.

In the end, people fall back upon their beliefs. Consider how different countries have behaved during the Covid-19 pandemic. Taiwan and Florida have populations of around 20 million people. To date, Taiwan has suffered 23 deaths from the virus. Florida has lost 36,000. lives (“The Threat Reflex,” by Michele Gelfand, Foreign Affairs, July/August 2021, pg.159.) Why the difference?

Michele Gelfan, a professor at the University of Maryland, and her colleagues have a theory. A society’s structure governs how it responds to a crisis. People in highly organized communities where they fear making mistakes are willing to obey rules and pull together during an upheaval. Citizens of a loose social order, one more tolerant and open to creativity, will resist restrictions despite a crisis. These free spirits are willing to expose themselves and others to increased danger. (Ibid, pg. 162)

Cultural norms aren’t the sole determiners of behavior. History plays its part, says Gelfan. Members of societies accustomed to numerous invasions or natural disasters will also show a greater tendency to adhere to rules for their mutual survival. Cultures with a history of few invasions or large-scale disasters have little experience with group cohesion. In a panic, the free-spirited are likely to gravitate to strong voices with simple solutions. More jails, more police, more restrictions that make us feel safe. Simply put, freedom dies as democracy erodes into populism and then to authoritarianism. (Ibid; pg. 163)

Tight societies have their weaknesses, too, which I won’t go into here. What’s important for Americans to recognize is that democracy is fragile and carries within it the seeds of its destruction.

One nation, younger than ours, seems to have escaped implosion and found a balance between freedom and cohesion: New Zealand. Though a loosely structured society, New Zealand chose to follow the rules of science. In doing so, it exhibited a “tight-loose ambidexterity,” says Gelfan. (Ibid, pg. 166.)

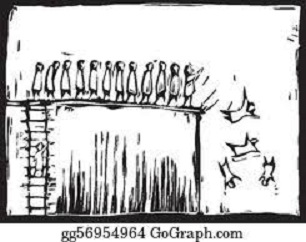

Americans can strike the same balance. We can work to find common ground. Or we can push ourselves to extremes until our final act is to fall off a cliff together.