My essay below first appeared in the ebook magazine Women Writers, Women’s Books on July 27, 2020. This is a reprint of that article.

EVERYONE HAS A STORY TO TELL

“Everyone has a story to tell,” said the woman seated opposite me at my retirement center. Somewhere in her 80s, she had the beauty of a Gibson Girl. A cloud of silver hair framed her pale complexion, and her eyes were the size of blue pebbles, though the color had faded. As she told me her story, her eyes strayed into the distance, as if images of her past were being thrown upon a far wall. I drained my coffee cup, not daring to make a sound, while she recounted stories of her youth–a period during World War II when, as a dancer, she entertained American troops on the Western front.

Though well into my 70s, I sat like a child before her, open-mouthed, dazzled by her adventures. She was proving her truth. Everyone has a story to tell. The question for most of us is how to begin and whom to address. Are the memoirs we write meant for friends and family? Or should the public be included? That decision is crucial from the start.

Friends and family are a willing audience. Relatives are curious about their predecessors. Why did Uncle Herman stop speaking to his brother? When did Cousin Ella become fearful of ponds? Grandchildren will turn the pages of a memoir salaciously, wondering if their grandparents ever kissed.

A family memoir is often linear in structure. The course of events unfold as they were lived–first this, then this, and then this. The vignettes march across the pages like a troop of well-rehearsed drummers. Introspection isn’t deep, though we may learn that Grandpa Rutherford favored eggs for breakfast because his mother served him porridge as a child.

Family members who hunger for tidbits about their heritage will tolerate a linear construction. The general public is likely to yawn. For them, a memoir must venture into a wider sea. No longer a teller of family secrets, the author sets a course for human understanding. What makes us laugh or cry? What dreams do we hold in common?

Organizing insights like these invite a structure more varied than a linear one. Book lovers who attempt a public memoir will have an easier time organizing their thoughts than the occasional reader. Bookworms make good writers. Call it transmigration or the process of osmosis, but those of us with well-worn library cards have been inhaling the writer’s skill simply by observing it—the way an infant learns to stand by mimicking its parents

For those of us less well-read, organizing material according to themes is a good plan: humorous stories, stories of disappointment, or those about overcoming difficulties. James Harriot’s format in All Creatures Great and Small also works. He salts sad stories between several happy ones.

Celebrities can ignore my advice and suffer no consequences. People will buy a famous person’s book out of curiosity or because they admire the individual. If the piece is boring, they will pass it along as a form of revenge to a neighbor–the guy whose dog likes to pee on your zinnias.

Most importantly, a memoir writer must be honest. Too many self-congratulatory remarks smack of narcissism. Expose your mistakes so your audience learns from you. If they do, they will love you for it. “We’re all mad here,” said the Cheshire Cat.

Everyone has a story to tell. If yours helps someone to reflect, laugh or shed a tear, you will have mastered the art of memoir.

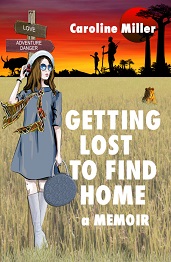

My upcoming memoir, to be published on November 1, 2023, makes a stab at all of the above. The narrative begins with an incident at my retirement center which provokes memories of a time in my earlier twenties when I spent four years abroad. In 1959, the ink was barely dry on my college diploma when I followed my fiancé to England. After two years spent struggling to adapt to life in a new country, the man I adored broke our engagement. Rudderless and far from home, I joined an English acquaintance to teach in East Africa.

I knew nothing about the political turbulence in that part of the world, an era when white colonial empires struggled to maintain their grip on indigenous populations. By the time I stepped off the boat in Cape Town, UHURU’s freedom cry had ignited the land. Even so, I little realized my coming-of-age story would mirror the joy, suffering, and danger of the birth of new nations. By the time I returned to the United States, I was a stranger in my country. I’d been transformed by my experiences yet well knew the value of making human connections.

Now, with my hair turned silver, I’ve chosen to retrace the journey that became a pilgrimage. Will readers connect with my story? Like every artist, I stand with my heart in my mouth awaiting their decision.