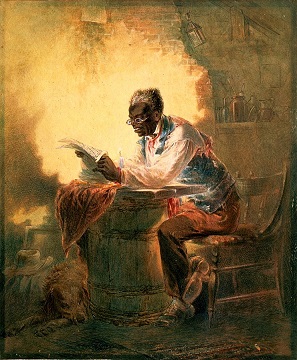

Courtesy of wikimedia.org

A woman at my retirement center has published a poetry collection. In her interview about the book, she refers to an essay by Mark Flannagan, a writer for Kirkus Review, in which he tries to define poetry. After a few attempts, he settles for one word: imagination.

Well, yes, I say to myself as I finish his remarks, but the description is incomplete. Flannagan’s choice is analogous to describing ice cream as cold. The statement is true but isn’t defining because snow and ice are also cold.

I’m not criticizing his effort. I could do no better. To create a poem, the artist does depend upon imagination. But so does someone who designs a sewer system or a comfortable chair. Every intellectual pursuit, science included, needs imagination. If the idea is to become concrete, it needs a vessel in which to materialize. Except for the visual arts where the medium is the vessel, human thought requires language if it is to be transferred–whether it takes the form of musical notes on a page or equations scribbled across a chalkboard.

Mathematics is the language of science and different from the words of poetry, of course. A poet revels in the sound as well the multiple meanings words convey. To write, “She had smoldering eyes,’ doesn’t send the woman off to the ophthalmologist. “Smoldering” is a metaphor. It draws our attention to a similarity between a fire’s embers and passion. Science created a different language to escape the multiple meanings of the poet’s words. To imagine and build a Mars rocket, their descriptions must be precise.

E=MC2, for example, expresses the relationship of matter and speed to energy. Elegant in its simplicity, its truth is unequivocal. No one mistakes the equation for a metaphor. What’s amazing, said physicist Eugene Wigner is mathematic’s “unreasonable effectiveness” as a tool for describing the physical universe.

What poetry shares with mathematics is a quest for the “Ah-Ha!” moment, an insight that increases our awareness. One quest science is exploring is a theory of a conscious universe. Panpsychism assumes the rungs on the ladder of consciousness are many but all matter has some capacity to feel. “While inanimate matter doesn’t evolve like animate matter, inanimate matter does behave…it responds to force.”

According to the theory, even the process of evolution expresses consciousness because it “chooses” to make changes with each iteration of a species. The human genome also expresses consciousness when it decides which genes to turn off and on.

Panpsychism isn’t a new hunch. Aristotle played with the notion and others followed. A subject normally reserved for philosophers of metaphysics and Buddhism, it has garnered scientists’ attention because they have new tools that can physically verify the airy thoughts of mathematics. How consciousness and matter interact–or if they interact–isn’t likely to be understood soon, though. To explore further, we await the dreamer who adds new vocabulary.

For those who have no wish to wait, there is an alternative. We can do as Buddha did. Find a quiet place to meditate. What is enlightenment, after all, but the intersection where imagination and knowing meet?

Or, we have a second way. To gain insight, we can pick up a book of poetry or fiction. I’ve long contended those arts dazzle the mind more than history.