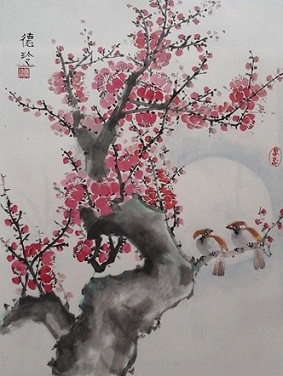

Courtesy of https://www.darlenekaplan.com/shop/

(On the eve of the first anniversary of my mother’s death at 104, I reprise a blog I wrote days before she died. I hope it will comfort those with similar losses in the past or yet to come.)

“I remind you, your parent isn’t actively dying.” The woman in charge of the assisted living facility where my mother resides spoke crisply as if intending to discourage my request for a visit. I wasn’t discouraged. By now, I’d lost patience with the medical parsing of words. At 104, my mother was close to the finish line and I hadn’t seen her for six weeks. When I promised to observe the necessary precautions, the woman relented and we agreed upon a time and date for my arrival. When the next Friday rolled around, I was ready and presented myself at the reception desk wearing rubber gloves, a head covering, and a mask.

A girl at the desk took my temperature: 98.1. “Proceed,” she intoned as if I were gaining entrance to the Great Pyramid of Khufu.

Fifty paces along the linoleum corridor, I found my mother. She was seated in a dining room reserved for private paying residents. It was larger than her customary accommodations, with a bank of windows that framed a garden scene plump with blossoms. A domestic worker sat nibbling her sandwich in one far corner. Otherwise, the cavernous space was empty. As long as the coronavirus remained a threat, guests didn’t share meals in congregate but ate from trays carried to their rooms. On the day of my visit, my mother was the exception.

Pale light from a cloudy day seeped through the glass panes where she was waiting for me. Outside, the flowering plum-tree, a mound of pink petals, seemed wilted by it before the light itself died in the dark corners of the room– diluted like a drop of milk in a bucket of water. An Andrew Wyeth scene, I thought.

She didn’t turn her head as I approached, though she’d been waiting for me. Her gaze was fixed on a far horizon as if she were drawn to an invisible demarcation line, not of geography, but one between the mind and the outer world–a horizon that beckons when someone is turned toward eternity.

Seating myself across from her but at a proper distance, I noted that the gravy pooled upon a hill of mashed potatoes in front of her had congealed. My mother hadn’t eaten that day nor, by the hollows in her cheeks, for several days running, I suspected. She wasn’t interested in food, she said as if to answer my unasked question.

“I’ve brought a peanut butter cookie,” I said, pushing the unwrapped confection toward her. The woman opposite me smiled, broke off a morsel, and put it into her mouth to show her appreciation. Then she slid the cookie back to me. “You finish It,” she murmured, rewarding me with a momentary glance.

Coaxing her to eat would be futile, I knew, so I let the silence fall between us as my mother returned her gaze to the window, past the plum-tree and the red camellia standing bellicose beside it, past the Rhododendron and the azaleas, budded but not yet in flower, past the clouds that hung like soggy cotton balls in the slate sky. My mother was fragile, bent, and barely aware of me. I call that actively dying.