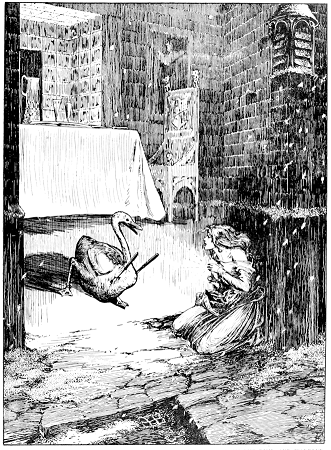

Helen Stratton’s “Litttle Match Girl”, courtesy of wikipedia.org

“Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” When F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote those lines in his novel, The Great Gatsby, he may not have been striving for poetry, but he exposed the truth–which is what great art does.

Lauren Larson isn’t an author but a journalist. Even so, her article for Towne & County gives us a glimpse of what upper-class struggles look like. Contemplate the simple task of deciding to move in with someone. Most of us would pack a suitcase or two and maybe a sleeping bag. The challenge for a pair of multimillionaires is different. One major question is how to combine a classical art collection with a lover’s penchant for Andy Warhol.

The solution is to pay handsomely for someone laughingly called an “art therapist.” This is an expert who blends treasures seamlessly. (“The Chattering Class,” by Lauren Larson, Town&Country, September 2024, pg. 56.)

My mother’s life was far removed from the pressing problems of collating surplus. She lived in Central America with a mother who was so impoverished that all she had to sell was her body. The nights her parent plied her trade, my mother hid in the shadows of alleyways, hoping that neither a pimp nor a revolutionary’s bullet would find her.

What my mother learned about the rich came from peering through the iron gates of large estates. Her cheeks pressed against the bars, she saw that money not only provided luxury but more importantly, it bought an island of safety. And like Nick Caraway, the narrator in Fitzgerald’s novel, she learned it was a lot easier to be morally upright when you’re not pinching and scraping to make a living.

A few years ago, I wrote that my mother argued with a principal when he insisted I attend a school in my neighborhood, one with a reputation for violence and drugs. Though still an immigrant, Mom wouldn’t bend to his decision. Day after day, she sent me back to the posh school with a note pinned to my collar. “My child deserves better.” Eventually, the exhausted administrator agreed.

Her strength taught me more than I learned in any classroom. Her lesson about barriers was one I will never forget. Decades later when I’d become a public figure, a journalist asked me why I kept mouthing off about the needs of ex-offenders and the homeless. “The poor don’t vote,” he reminded me. Cynical as his remark was, it was also the truth. What’s more, I knew why. The poor don’t have hope and joy.

In election years, a person hears a lot about the Middle Class. My high school journalism teacher laughed when he said everyone identified as Middle Class because no one wanted to admit they were poor. But facts don’t lie. We have too many poor people in this country, some of them having fallen from the Middle Class. Between 1971 and 2021 membership in that cohort dropped from 61 to 50%. Those who have fallen make up part of the 31.9 million impoverished folks we pass in the streets but fail to see. 31.9 million! That’s a staggering statistic for the world’s richest nation.

My memories of poverty run raw in my veins, so I bristle when politicians pander to the Middle Class, describing them as “hard-working people.” Well, let me tell you about the very poor. They work hard, too. They don’t vote because they can’t take time from work to go to the polls. Or, they don’t have transportation that will take them to their precincts. Or, if they have the carfare, they’d rather buy bread.

Trust me. It’s hard to be energized when those in power see you as either lazy or a criminal. It’s impossible to feel welcome when the hardworking Middle Class doesn’t see you. This November, I’ll vote for candidates who don’t beat their chests about the Middle Class. I’ll vote for those who have plans to lift into the light those too long lost in the shadows of scarcity.