Courtesy Amazon.com

Rebecca Solnit, the author of Men Explain Things to Me, tickles my funny bone. She has a sharp wit and a sharp pen which she exhibits regularly as a columnist for Harper’s. In addition, she is well-versed in a number of subjects, having written about the environment, landscapes, politics, memory and a history of walking, among others. Award winning and prolific, I had to admire her chutzpah when I landed on her Amazon page the other day. There, she advises shoppers to purchase her book elsewhere, at “your local independent bookstore, Powells.com, Barnes & Noble online” because she explains, she “has some large problems with how Amazon operates these days.”

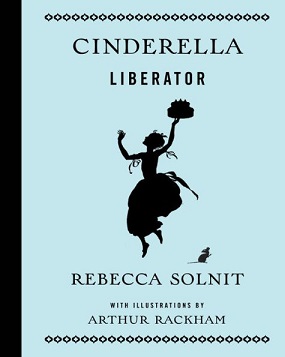

Being a woman unafraid to poke a lance into the powerful, I was eager to read her just published, souped up version of Cinderella: Cinderella Liberator. Naturally, I hurried to my local Powell’s bookstore to purchase it.

The revised fairy tale consists of 27 pages, including some lovely silhouette illustrations by British illustrator, Arthur Rackham, making it an enjoyable and quick read. If I expected the story to be ripe with satire, I was disappointed. Solnit stayed close to the classic tale. All the familiar characters appear. The step sisters and stepmother are as wicked as of old. They give Cinderella not the slightest thought as they swan off to a ball. Happily, the fairy god mother arrives on schedule. With the few tools at her disposal — a pumpkin and an assortment of field creatures — she produces her miracle: a glass carriage with four horses and, in this version, a coachwoman. Another swipe of the wand transforms Cinderella’s rags into a ball gown. Then, to complete the ensemble, she provides her charge with a pair of glass slippers.

The evening unfolds as the classic tale must. The Prince, enchanted by his graceful dance partner, searches for her from household to household once he discovers she has disappeared. His only clue is one of the glass slippers she left behind. But when the pair at last find one another, the plot takes an abrupt turn. Instead of falling into one another’s arms to live happily ever after, each tells the other his or her heart’s desire. Cinderella doesn’t want to be a princess. She wants to be a baker. Relieved, the prince admits he’d like to trade his silk garments for a farmer’s rough tunic.

The pair agree to set each other free, while vowing to remain fast friends. The magic of their generosity surprises those around them. Others begin to follow their example, among them Cinderella’s wicked step sisters. After seeking forgiveness from their relative, the pair go off to find their bliss, one as a dressmaker and the other as a hairdresser. Cinderella’s example has taught them to feel no shame in honest labor. What matters isn’t riches but friends.

One critic praised Solnit for having “transformed a beloved but morally outdated classic into a powerful narrative of female agency with a moral compass we can all believe in.” Of course, that is too pat. Cinderella always was a transformative character, a heroine who triumphs over greed with patience and hope.

What Solnit has done is cast the net of personal freedom wide enough to include everyone, imbuing them with the dignity that comes from having choice in their lives To create a harmonious society requires for more than one individual to be free. All individuals must be free. Sharing must be at the heart of a society if everyone is to be friends. In the 21st Century, with the earth’s resources dwindling, we might all gain from this story about sharing.