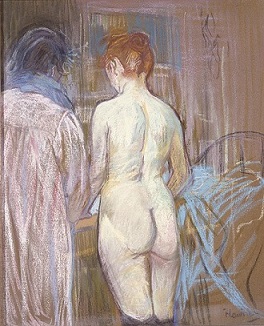

Toulouse-Lautrec painting courtesy of wikipedia.com

In Costa Rica, or Panama or Honduras, wherever they’d migrated, when the piggy bank was empty, my maternal grandmother worked shifts in a local brothel to put food on the table. She wasn’t a regular sex worker but rented rooms by the hour. If she couldn’t afford the fee, she’d toss my mother, a child as young as 7, from their dwelling and onto the streets to hide in the dark until the business was done. Sometimes, my grandmother didn’t call her until the wee hours of the morning, which left my mother too sleepy to attend school. The neighborhood was crime-ridden, so catching a few winks on a public bench was dangerous, particularly if the country of residence was in the midst of a revolution and a timpani of gunshots broke the silence without warning.

If I am honest, I suspect my mother may have resorted to a similar desperation a time or two. I was never turned out to the streets but once I recall she brought home a stranger and before shutting the bedroom door after he’d entered, she warned me to stay in the kitchen and be quiet. Being young, I did as I was told. My mother and I were a team, after all.

Too young to know the ways of the world, I nevertheless sensed my mother’s shame and spent my silence wrapped in volcanic anger I couldn’t explain. And then there was the evening when she almost died because she’d attempted to give herself an abortion.

Should I be ashamed to tell the stories of the women in my family? No. The shame lies with the few who amass most of the world’s fortune and condemn 689 million people to live in squalor. The shame also belongs to those who “tut-tut” about morals and turn a blind eye to the injustice of poverty. No one should live in a world where his or her body is the sole asset.

For most of my adult life, I have lived among colleagues who are unaware of the invisible poor. I can’t blame them. These are the people who make the least trouble. They don’t steal or sleep in tents on the streets. They are too terrified of the authorities. They use their bodies to get by.

Today, a dark industry flourishes around these destitute. Though it brings in billions of dollars across the globe, these illegal workers have few luxuries and fewer protections. That, at least, should be changed.

There is some movement, though it is glacial. In 2003, New Zealand decriminalized prostitution and gave the sex workers rights. Places in Europe haven’t gone as far, but they’ve made it unlawful for the police to beat them. Or, these workers are now entitled to refuse a client and seek damages for reprisals. Four states at home, New York, Maine, Vermont, and Massachusetts have introduced legislation to decriminalize the trade. (“Empowered Workers, by Sessi Blanchard, ACLU Magazine, winter 2021, pg. 8.) Whether those prone to tut-tutting” will prevent their passage remains to be seen.

Britain, a country that tracks dark money, estimates billions of dollars circulate throughout its economy each year. If the plight of those trapped in the trade is of little interest to some, the loss of taxable income should provide a practical reason to bring prostitution out of the shadows. As for the moral impact on society, let’s be honest. Sex workers have done more to sustain the well-being of the country than ever did our 45th President, Donald Trump.