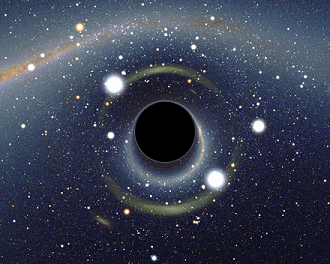

Spinning on a blue marble at the edge of our galaxy in infinite space, we humans continue to assume we have control over our lives. Yet, almost every day science makes a discovery that astounds us. Recently, astronomers learned they were wrong in their understanding of black holes. Since Einstein, they’ve allowed us to think such entities were vacuums in space, sucking up matter and light to be banished from our universe forever. They now know that understanding is wrong. Like a mailbox stuffed with Christmas catalogs, black holes have limits. Theoretically, they can spit an overflow of matter and light back into our dimension. Black holes, it seems, can both murder and create. To scientists, that signals an underlying reality beyond the void. Black holes, it appears, are open systems rather than closed ones.

Spinning on a blue marble at the edge of our galaxy in infinite space, we humans continue to assume we have control over our lives. Yet, almost every day science makes a discovery that astounds us. Recently, astronomers learned they were wrong in their understanding of black holes. Since Einstein, they’ve allowed us to think such entities were vacuums in space, sucking up matter and light to be banished from our universe forever. They now know that understanding is wrong. Like a mailbox stuffed with Christmas catalogs, black holes have limits. Theoretically, they can spit an overflow of matter and light back into our dimension. Black holes, it seems, can both murder and create. To scientists, that signals an underlying reality beyond the void. Black holes, it appears, are open systems rather than closed ones.

How this new information affects human life is unclear, but Donald Trump should rejoice. He’d love to redo the 2020 election.

But as I said at the start, though the universe is in flux, we humans behave as if we had a degree of control. The U. S. government, for example, hires prognosticators whom they imagine can peer into the future in a way that will inform the present. “A Better Crystal Ball,” by Peter Scoblic & Philip E. Tetlock, Foreign Affairs, pgs. 11-18.) At the moment, these seers use two methods for predicting upcoming events. The first examines comparable scenarios from the past and tries to discern which of them are the most likely to reoccur. The weakness of this strategy is that it fails to anticipate the unexpected. Trump’s plan for a second term in the White House was unsuccessful because he was unable to foresee the arrival of Covid-19.

The second method isn’t restricted to examining past events. It considers anything imaginable. Once this universe of the possible is ascertained, the task is to whittle outcomes down to reveal the probable. Unfortunately, imagination offers too panoramic a view for accurate whittling, so some experts suggest forecasting the future might require a combination of the first and second methods.

Of course, we must take into account quirks of the human brain. People tend to cherry-pick data according to internal preferences. The mind can imagine many scenarios but choosing the probable ones can fall victim to psychology. (Ibid pg. 17.) The polls in the recent 2020 election show us the degree of human error. Many hoped or feared a blue wave was upon us.

Knowing we understand little about black holes and prognostication, I am left with a question. Why, during this pandemic, have so many Americans refused to wear masks? What quirk of imagination allows them to suppose they will escape the virus or fail to infect loved ones? Perhaps they have some 4th method of prognostication? Perhaps it is one that permits them to attend political rallies, large parties, or crowd into airplanes to visit grandparents during the holidays with no fear of dire consequences. If so, I wish they’d share this knowledge with others as too many of us are dying.