Selfies on social media platforms are common. Hold a cell phone at arm’s length, choose a flattering angle from which to shoot, then share the image with the world. The picture represents a self-impression: the face we create to meet the facts that we meet.*

Selfies on social media platforms are common. Hold a cell phone at arm’s length, choose a flattering angle from which to shoot, then share the image with the world. The picture represents a self-impression: the face we create to meet the facts that we meet.*

Our self-image is largely an internal one, a mixture of looking in the mirror and observing how others react to us. It is the way we distinguish ourselves from others–“a fragile illusion that needs constant reinforcing” and if neglected can lead to isolation and possible mental illness. (“Help! I Can’t Stop Staring at My Own Face,” by Meghan O’Gieblyn, Wired, April 2021, pg. 25)

In his poem, “To a Louse,” Robert Burns opined on what life would be like if we could see ourselves as others see us–as he does with the lady in his poem. She wears a starched, white cap to church but it fails to hide the lice in her hair. Ignorance is bliss, as they say.

Even so, to project our image, we mortals plunge into new technology as if it were a box of chocolates and never seem to fear the consequences. Zoom is our new way of keeping in touch with each other. But unlike a selfie, in this medium, we lose control of our self-image. Every gesture, every unguarded expression, every shift in tone gets reflected so that we are forced to confront ourselves as we flow through time. Through this looking glass, our image can be less graceful than imagined.

Most of us can survive exposure in a chat room, but new technologies pose a greater danger than a frayed ego. Consider Domain Awareness. These are elaborate systems that coordinate massive amounts of data through algorithms. Domain Awareness is crucial to self-driving cars. These vehicles require more knowledge than a map and a destination. They must consider road conditions, traffic levels, a chicken crossing the road, and an almost infinite number of unexpected changes that can occur while driving from point A to point B.

A few years ago, such calculations were inconceivable. Today, they are child’s play. While each advance opens new frontiers and provides greater conveniences, consider the consequences when these new systems focus on ordinary citizens.

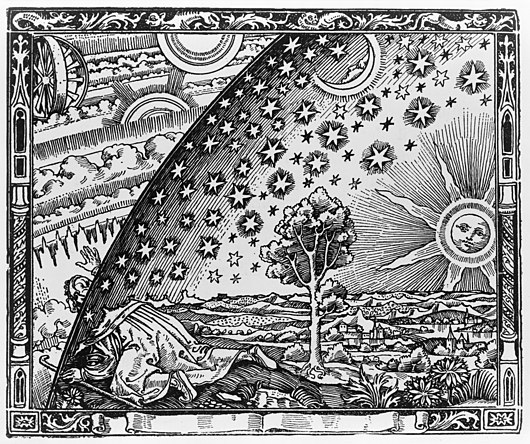

Already, surveillance exists which can identify an individual in a crowd from a distance of two football fields. If facial recognition isn’t clear, identifying tattoos will do, or an individual’s unique heartbeat. (“God View” by Arthur Holland Michel, Wired, April 2021, pg. 50) Now add Automated fusion. It allows many data points, like the ones I’ve suggested, to be integrated. CCTV and smartphones are the tip of the iceberg. Add Google’s ability to comb the internet and the horrifying potential of an “all-seeing eye” in society, one that never sleeps, becomes manifest. For a preview of what that society would look like, think of the film, Minority Report. “To the extent that you do not trust your government, you do not want your government to build these systems. “ (Ibid, pg. 55.)

The warning may be too late because work is underway to fully integrate data systems. Look no further for an example than the innocent family in Afghanistan who was blown to bits because the integration, still in its infancy, failed. As horrendous as that failure seems, consider a future when the system always succeeds. Further, be dismayed that no laws at either a national or international level exist to proscribe how one should use these innovations.

Alert citizens must have a say in the matter. At the moment, too many prefer to bay at the moon, championing their right to spread infectious diseases. If they don’t wake up, the only place left for any of us to find personal freedom will lie in the spaces between the data points of an algorithm.

*The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T. S. Eliot