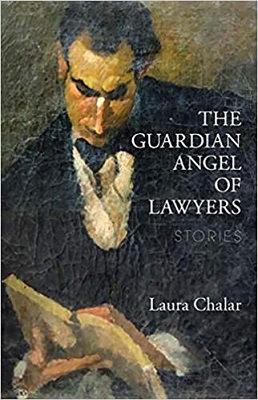

Courtesy of amazon.com

I hadn’t ordered the book. It was sandwiched between two purchases I’d made from Alexander McCall Smith’s series, The Number 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency. Was this a mistake in the shipment I wondered or a bonus of some kind? Not knowing, I set the volume aside and plunged into my new reading, forgetting the stowaway entirely.

Three months later, however, under quarantine from Covid-19 and being short on decent reading material, I rediscovered the forgotten title: The Guardian Angel of Lawyers, translated into English by its Uruguayan author, Laura Chalar. According to the jacket, she practices law in that country.

Curious, I turned to the index page and discovered the book was a collection of 12 short stories published by a small press in Connecticut. That didn’t bode well. Even so, with little else to occupy me, I settled into my leather chair and turned to the first story, letting the pool of light from my reading lamp focus my attention.

The first tale, being a matter of a few pages, went down well, so I turned to another and then another until the face of the regulator clock, its hands pointing upward between 11 and 1 in the evening, seemed surprised at the lateness of the hour. Where had time gone?

My experience poses a question. What makes a best seller? In my opinion, Chalar’s book deserves to be one, being superior to many for the beauty of its phrases and the depth of detail they provide. Consider the opening line of “Fire and Ash.” Diego Mauricio, professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Buenos Aires, pours himself a coffee in a plastic cup, wraps the sticky croissant in a napkin, and follows the sunny corridor until he Is on the street. That long, languid and lazy sentence, at once sensual and tactile, foreshadows a sequence of events that will turn an ordinary day into one fraught with surprise and the whiff of regret. Like the onomatopoeic device of that first sentence, the author’s prose often approaches poetry.

Though set in modern times, the stories have a medieval atmosphere. Words perform the work of illumination in that they illustrate the subtle ironies of ordinary life as it might be lived in any time and any place. What matters are the ironies, not the resolutions. We meet each of Chalar’s characters at inflection points which invites them to examine an incident that has the power to create insight or which allows them to look away. It little matters. They will never be the same, though they may fail to understand why. The reader is the one who benefits. Irony exposed may make us sad, or we may choose to smile. That, too, is an inflection point where we have an opportunity to learn.

I recommend this book and consider it a black eye on the publishing world that Chalar’s art has received slight attention.