She’s a star within the Evangelical community, but I won’t identify her for reasons that will become clear. We met decades ago when I was an elected official. Though I am an atheist, I treated members of the religious right with the same courtesy I gave to Mothers Against Drunk Driving (Madd) when they chose to give public testimony. That’s how it should be.

Besides, I understood their reasoning and knew it was heartfelt. If a fertilized ovum is a person, then it has a soul, and destroying a soul would be a sin. I never interrupted to comment that soul and sin had no meaning in secular law. Nor did I point out their logic was flawed. If a soul is immortal, then destroying it would be impossible.

What Evangelicals and I do agree upon is that society requires moral underpinnings–an admission that explains how I came to meet a celebrity of the faithful.

I was late in arriving at the luncheon to which I was a guest. Sliding into the chair reserved for me, I offered a general apology and then introduced myself to the woman seated at my left. She told me she’d flown into town that day to be the keynote speaker at a spiritual rally that evening. A woman in her early thirties, she bore a strong resemblance to Doris Day, her smile welcoming and crowned by a row of white teeth. Observing that she was confined to a wheelchair, I never doubted that she lived a life of courage.

We chatted over salads and I learned she was traveling across the country, fundraising to provide wheelchairs for the needy. My ears pricked up like a dog’s at the sound of an electronic can opener when I heard her. Many of my constituents could have used a wheelchair. I suggested we might work together.

The woman shook her head to reject my suggestion. Her wheelchairs, she clarified, were intended for potential church members.

“You use the chairs to recruit the poor, you mean?” If I’d sounded incredulous, she didn’t get my drift. Instead, her lips parted in a dazzling smile.

“Exactly!”

By some miracle, I managed to hold my tongue, though I wanted to reply that the church enjoyed tax subsidies, a fact that should entitle believers and non-believers to assistance. Using public money for private purposes was dishonest.

Nonetheless, by the time I parted from her, our salads finished and the bread basket emptied, I confess I liked the woman. My reaction to her duplicity, therefore, was to turn inward. I knew I should have spoken out about the misuse of public funds. Yet, for the sake of peace, I’d said nothing. Returning to my office in the plashing rain, I fell into a blue funk.

A lie can be either good or bad depending upon circumstances, but it is always a violation of the truth. Either way, we humans have practiced verbal deception since we developed a jaw that enabled speech.

Many women oppose men-only clubs because absent a feminine voice, they encourage masculine delusions. At least that’s true for one male. He admitted that these watering holes were places that allowed men to exchange ideas and learn from each other without being “canceled” for having the “wrong opinion.”

Many have said a democracy without an informed electorate will fail. When we allow lies to co-mingle with truth, we empower subversives, and that’s why, according to Eric Hoffer, The character and destiny of the group are often determined by its inferior elements.” (“The True Believer,” HarperPerenial, 2002, pg. 24.)

To prevent corruption, people should confront those who use free speech to pervert facts. That much is obvious. But a citizen’s responsibility goes deeper. Rooting out the lies we tell ourselves helps us become patriots.

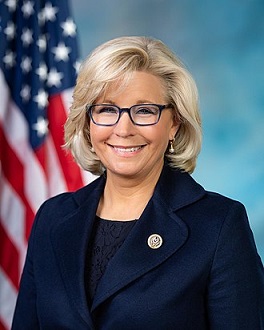

Liz Cheney, recently rejected for the Gerald R. Ford Medal for Distinguished Public Service, is a patriot. She refused to deceive herself in the rough and tumble of politics, though she might have benefited. Instead, she defended the truth and it cost her– unlike the Evangelical celebrity who used charity to be exploitative. And, also, unlike me who saw the deception and said nothing.