Courtesy of wikipedia.org

I’ve told this story before. Theodore Dreiser gave a lecture at a university where a young man seated in the audience was writing his doctorate on Dreiser’s, Sister Carrie. After the presentation, the student collared the author to talk about his dissertation, hoping to validate his theories. Dreiser listened without interruption until the student had finished. In the silence that followed, Dreiser’s eyes widened. “Did I do all that? I never knew.”

Theodicy is the word that describes this phenomenon. It’s the notion that no creator is fully in control of his or her work, not even God. How else are we to account for Satin? And please, no yammering about our ignorance of God’s will. If we don’t know His will, then we can’t be certain there is one. By outward appearance, Satan poses consternation to both God and man. If that isn’t the case, our Lord exposes Himself to charges of both masochism and sadism.

About theodicy, one writer adds, “It is an unfortunate but reliable truth that creators tend to recognize their oversights only after it’s too late to undo them.” (“Start,” by Meghan O’ Gieblyn, Wired, June 2022, pg. 28.) The internet is an example. Visionaries saw their invention as a vehicle that would share knowledge and set truth free. The plan succeeded during Arab Spring. Too quickly, however, those with more ignoble ambition saw that these same communication channels were capable of carrying disinformation. Vladimir Putin uses the web to mislead his citizenry about the course of his Ukraine invasion, for example.

Today, communication channels once envisioned to belong to everyone are in the control of six major platforms: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft Netflix, and to a lesser degree, Twitter. (Ibid), pg. 29) An internet without them is hard to envision. Unfortunately, centralized power tends to narrow our vision rather than widen it. People see what these corporations want them to see. In exchange for a limited horizon, we subject our personal information to data mining, mass surveillance, and ideological polarization. (Ibid, pg. 29) Writer Meghan O’ Gieblyn concludes, “… ‘visionaries’ of our age are not divine entities but ordinary humans who have stumbled upon magical instruments they do not fully understand.” (Ibid, pg. 20)

When lies pass for the truth, it’s little wonder that scientists who dedicate their lives to veracity are worried. Says one, “I don’t remember feeling as horrified about the need to actually defend science in our lifetime as in the last four or five years.” (Catalyst, Vol. 22, Spring 2022, pg. 20) Dr. Anthony Fauci’s experience during the covid pandemic is a depressing example of what the expert means. A physician-scientist, immunologist, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Chief Medical advisor to the President, he has been the target of know-nothings who fail to grasp how viruses work. Their ignorance has exposed our society to so many iterations of the disease that, despite vaccines, we can no longer hope to rid ourselves of the affliction. Instead, we are condemned to live with it.

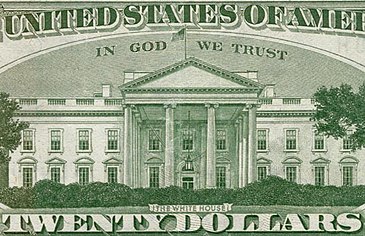

Having lost our war against covid, we seem ready to do the same in our efforts to control climate change. Little wonder those who prefer to spend their lives peering through microscopes and telescopes are shifting their attention to politics. They hope “increase the role of science and scientists in democracy-building efforts.” (Ibid, pg. 7.) To that end, The Union of Concerned Scientists has launched a school for science advocates to combat the plethora of misinformation. Unfortunately, American culture has never shown respect for information. We’d do well to remove “In God We Trust” from our currency and replace it with, “My ignorance is as good as your knowledge.” – Isaac Asimov –