Courtesy of wikipedia.org

Pericles, an Athenian statesman born in 495 B. C., credited much of his medical knowledge to witches. (Man Made God, by Barbara G. Walker, Stellar House Publishing, 2010, pg. 278.) As women historically have been keepers of hearth and home, it’s reasonable to suppose their remedies for ailments were passed down from one generation to the next, forming a body of knowledge that later was vilified as witchcraft.

In the Middle Ages, the Catholic church took a hostile posture toward women’s healing powers. Their concoctions to treat warts, rashes, and headaches worked. Priest armed with holy water and prayers proved to be less successful. To defend their authority as healers, priests had to eliminate women practitioners. Fortunately, for them, the Inquisition created a path.

Many women the priests charged as witches were wealthy, widows whose lands and possessions the church coveted. If found guilty, the accused’s property fell to the holy order. Greed became a strong motive for rooting out witchcraft, a fact which led a French Inquisitor in 1375 to opine he might run out of victims. (Ibid, pg. 278)

What gave these proceedings the fig leaf of legitimacy was the rule that required a woman to confess before she could be punished. Torture, therefore, became the means for obtaining confessions and the methods grew so numerous, they were collected in the church’s official manual: Malleus Maleficarum. Browsing through its pages, a reader is left in no doubt about why “no one was ever declared innocent.” (Ibid, pg. 279)

Today, the practice of persecuting witches is alive and well. It thrives in India, for example. According to statistics, at least one accused woman dies in that country every third day. . (A Death Every Third Day,” by Arundhati Nath, MS, Summer 2021, pg. 17.) The reasons for the accusations are classic: “…jealousy and/ or land-grabbing disputes [are] motives.” (Ibid, pg. 17.)

In 2018, India created a law to protect women from witchcraft charges but it has had a small impact. Centuries of institutionalized persecution are hard to erase. In addition, other abuses against women abound–child bride marriages, domestic abuse, and sex trafficking.

Why do patriarchal societies persecute women to such a high degree? At one point in human history, scholars think men and women were equals, but that roles changed in the agrarian era. Others look to biology –which may explain why talk of reproductive rights raises hackles to this day.

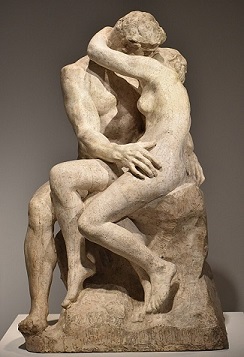

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, thought part of the problem might stem from the conflict young males face as children. Freud called the condition the Oedipal Complex. He defined it as a time when a boy so loves his mother that he sees himself in competition for her attention with his father. Freud concluded once the boy learned to identify with his father as a male, the conflict was resolved.

Should we believe the good doctor? Does this conflict in males resolve itself or does it become manifest in other ways? So far, the literature seems to focus on what happens to women when men objectify them as sexual objects. A google search on men’s inner sexual conflicts has turned up scant material. More exploration seems appropriate. How do men internalize their dual roles as sons and lovers? If we knew that answer, we might understand why patriarchy has become a sanctuary for female exploitation.

Women make poor combatants in this war between the sexes. As companions and mothers, their specialty is love. So far, that emotion has done little to calm the roiling patriarchy. We need to learn more.